We're living longer than ever…but suffering more pain, depression and illness as a result

- From 1990 to 2010, the global average age of death rose from 59 to 70, with women outliving men by about five years

- Scandinavia and Australia have the longest life expectancy, while Africa and Russia are among the lowest

- But living longer means we are suffering health problems that cause us years of pain, disability and mental distress, says landmark study

Life expectancy around the world has soared, but we are now living with health problems that cause us years of pain, disability and mental distress.

This ‘devastating irony’, as researchers describe it, is one of the key findings of a landmark study assessing the global health in the history of medicine.

From 1990 to 2010, life expectancy continued to increase in most parts of the world. The average age of death rose from 59 to 70, with women outliving men by about five years.

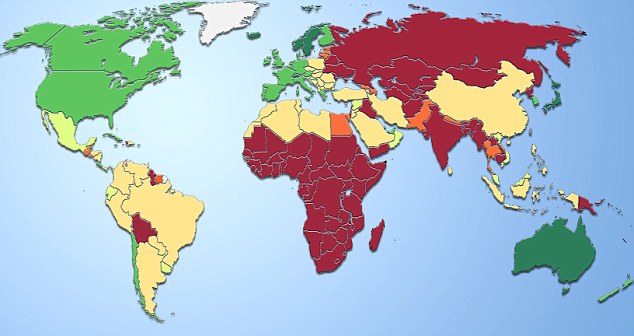

The map below highlights the average life expectancy by area, with Scandinavia and Australia having the oldest populations.

World life expectancy map

The map shows the average life expectancy for men around the world in 2009. The overall global life expectancy has risen from 59 in 1990, to 70 today.

However, as the population has aged, the number of years that people live with chronic diseases and disabilities, such as back pain, diabetes, arthritis and depression, has also risen.

Today’s major health problems now are diseases and conditions that don’t kill, but make us ill. We now live longer with more health problems that cause pain, impair mobility, and prevent us seeing, hearing and thinking clearly.

These consequences of an ageing population were compiled by researchers from more than 300 institutions from 50 countries around the world. They took data from surveys, censuses and hospital records and used computer models to estimate how long people live and how healthy they are.

Smoking and alcohol use have also overtaken child hunger to become the second and third leading health risks

The Global Burden of Disease study, led by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at Washington University, found that countries face a wave of financial and social costs from rising numbers of people living with disease and injury.

Among other findings are that while malnutrition has dropped down the rankings as a cause of death and illness, the effects of excessive eating are taking its place.

Smoking and alcohol use have also overtaken child hunger to become the second and third

leading health risks, behind high blood pressure.

Over three million deaths globally were attributable in 2010 to excess body weight, more than three times as many as malnutrition.

‘We’ve gone from a world 20 years ago where people weren’t getting enough to eat to a world now where too much food and unhealthy food – even in developing countries – is making us sick,’ said Majid Ezzati of Imperial College London, one of the lead researchers.

The research also found that of 52.8 million deaths globally in 2010, chronic diseases took the highest tolls.

About 12.9 million deaths were due to stroke and heart disease – conditions exacerbated by eating and drinking too much, smoking and taking too little exercise – and eight million were from cancer.

HIV/AIDS killed 1.5 million people in 2010, and tuberculosis, another infectious disease, killed 1.2 million.

While child mortality has decreased, there has also been a startling 44 percent increase in the number of deaths among adults aged 15 to 49 between 1970 and 2010. This is partly because of increases in violence such as homicide and traffic accidents and the AIDS epidemic, the researchers said.

‘Very few people are walking around with perfect health, and as people age, they accumulate health conditions,’ said Christopher Murray, the IHME’s director. ‘This means we should recalibrate what life will be like for us in our 70s and 80s. It also has profound implications for health systems as they set priorities.’

The study, was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and published as seven papers in The Lancet medical journal.