As a person who grew into adulthood without a father, I gravitated toward those books that taught me something about the experience of having (or not having) an older male presence in the home. I was particularly drawn to representations of fatherhood in Chicano literature because the cultural and social settings made it easier for me, a Mexican immigrant, to imagine the paternal affection that I craved. I always suspected that having such a relationship was a complicated one and that there were as many setbacks as there were rewards.

Reading the following compelling books by Chicano authors about fathers and father figures confirmed those assumptions but, without fail, one thing was abundantly clear: no matter how challenging that fatherly bond, it was never lived without love.

1. Ron Arias, Moving Target: A Memoir of Pursuit, Bilingual Press, 2002.

Arias’ training as a journalist helps him begin to solve the mysteries of his father’s past. While trying to locate him years after he had disappeared, Arias discovers that his father has passed away, so he conducts an investigation to piece together who this man really was and what were the motives behind his decision to leave his family. Arias’ memoir uncovers a startling speculation about his father’s role in WWII and in the Korean War, then learns new details about his parents’ strained marriage and about his mother’s suspicious death. In the end, Arias doesn’t find the answers he seeks, but does have a better grasp on his father’s life journey and elusive nature.

2. Ana Castillo, My Father Was a Toltec and Selected Poems, Anchor Books, 2004.

Growing up in the Mexican/ Chicano neighborhoods of Chicago in the 1960s, Castillo finds solace and sadness in the fact that her father had struggled with similar racial tensions. As a young man he joins a street gang, The Toltecs, and finds strength among other troubled youth. Though this was an empowering act in the short term, in the long run it led to a difficult adjustment with adulthood and a family life. Castillo pays tribute to his heyday but doesn’t shy away from calling out his failings as a husband and father in this evocative and energetic book of poems that frequently captures the code-switching language of a dynamic multicultural space.

3. Denise Chávez, The King and Queen of Comezón, University of Oklahoma Press, 2014.

Known for her humorous and provocative representations of small New Mexico border communities, Chávez introduces her readers to Comezón, the appropriately named town because its citizens all seem to have an itch—an unfulfilled desire for something or someone.

RELATED: Summer Reads: 7 Latino Books About Mothers

The king of Comezón is Arnulfo Olivárez, who spends the course of this quiet but powerful novel visiting various people and places in his dusty weather-beaten kingdom, trying to come to terms with his regrets before he too succumbs to time. The queen is arguably the town itself, the collective consciousness and identity of a community that fills Arnulfo with strength and pride.

4. Victor Martínez, Parrot in the Oven: Mi Vida, HarperCollins, 1998.

Set in the barrio of a central California city, this coming of age young adult novel is told through the point of view of Manny Hernandez, a Chicano adolescent who simply wants to prove to himself, and to his father, that he’s ready to become a man. Manny’s numerous attempts include joining a boxing gym, joining a gang, and even awkwardly romancing a crush, but his true test is in confronting his alcoholic father whose violence is breaking the family apart. The more Manny strays the more he understands how ill prepared he is for the streets and that the only way to grow into healthy adulthood is to battle the demons of abuse and low self-esteem at home.

5. Luis J. Rodríguez, It Calls You Back: An Odyssey Through Love, Addictions, Revolutions, and Healing, Touchstone Books, 2011.

This memoir about a former gang member and drug addict leaving “la vida loca” and becoming a revered activist and award-winning author is both heartfelt and inspiring, particularly as Rodríguez looks toward his responsibilities as a husband and father to stay on the correct path. But when his own son loses his way, winding up in prison like Rodríguez once had, Rodríguez sets off on a more difficult quest than the first: to save his son using the power of the word, respect for community, and love of family. The raw honesty of Rodríguez’s journey will make this memoir as much of a classic as his first, “Always Running: La Vida Loca: Gang Days in L.A.”

6. Richard Rodriguez, Days of Obligation: An Argument with My Mexican Father, Penguin Books, 1992.

Never one to shy away from controversy or provocation, Rodriguez considers the concept of fatherhood through the bittersweet legacy and heritage of the fatherland, in this case Mexico. Unlike Gloria Anzaldúa’s border theory of inclusion and intersection, Rodriguez argues that the reality of the Latino experience and identity is to negotiate a series of dichotomies, which are constantly in conflict: the North versus South, Past versus Present, etc. Though many might not agree with his assessment, his startling observations about culture and ethnicity are important contributions to the current political climate.

7. Benjamin Alire Sáenz, A Perfect Season for Dreaming (illustrated by Esau Andrade Valencia), Cinco Puntos Press, 2008.

Sáenz’s moving picture book takes an intimate look at the endearing bond between a grandfather and his granddaughter. Octavio Rivera, nearly a century old, has been having imaginative dreams lately and he understands that only his beloved Regina will treasure them as much as he. The surreal yet beautiful language of dreams becomes their private communication, and Regina senses that this is her grandfather’s final gift to her as he prepares to leave the living. Andrade’s dazzling illustrations do justice to Sáenz’s touching story about this unique familial relationship.

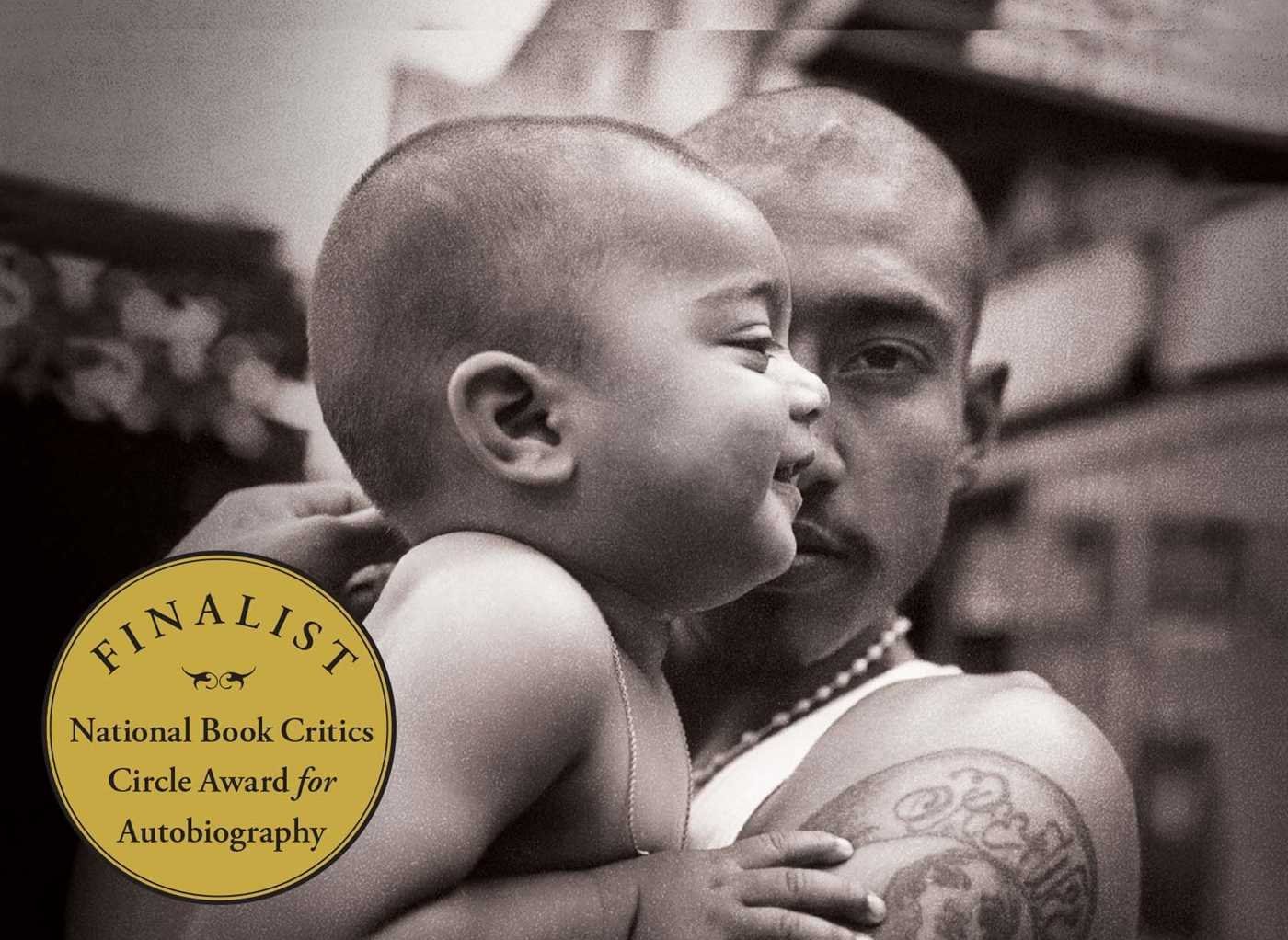

8. Luis Alberto Urrea, Vatos (photographs by José Galvez), Cinco Puntos Press, 2000.

This collaboration between the writer and the visual artist came about when Galvez heard Urrea read “Hymn to Vatos Who Will Never Be an a Poem,” which celebrated the lives of working class men from the barrio, much like Galvez’s series of photographs had been doing—making visible images depicting the heartaches and triumphs of Chicano masculinity. Partnering photos with lines of the poem, this book presents a vibrant and complex portrait of Chicano identity, shattering stereotypes and highlighting the expansive emotional landscape that Chicanos inhabit.

Source: NBC