Why Mexicans Love Moz

Why Mexicans Love Moz

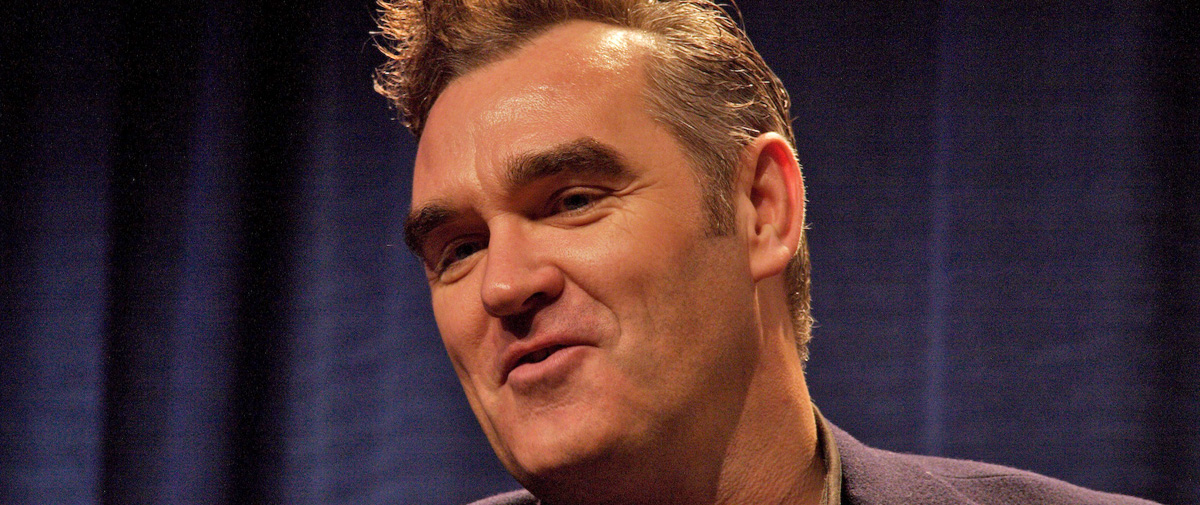

Yesterday, Los Angeles celebrated Morrissey Day.

“Los Angeles embraces individuality, compassion, and creativity, and Morrissey expresses those values in a way that moves Angelenos of all ages,” Mayor Eric Garcetti said in a statement. “Morrissey Day celebrates an artist whose music has captivated and inspired generations of people who may not always fit in — because they were born to stand out.”

Scholars, writers, cultural anthropologists, sociologists and generally curios people have attempted to find the origins and reasoning behind the connection between Latinos and Morrissey. They have yet to find a concrete answer, and it is likely that there isn’t one. There’s a very good chance there’s not a singular moment that served as the catalyst for that connection, but rather an overall collection of happenings and cultural shifts that have built this diehard following. That includes the influence of rock and roll on 1950’s pachucos and greasers assimilating to American life.

However, Moz, as he’s lovingly referred to, has his thoughts on the deep love between he and his Latino fans.

“Latinos are full of emotion, and whether its laughter or tears, they are ready to explode, and they want to share their emotion, and they want to give, and show, and show,” he once said in an interview. “I think that’s the connection because when I sing, it’s very expressive.”

Mexicans stand tightly together, heavily tattooed and full of heart, loudly singing along with Moz whether at a concert or in our bedrooms. It’s how we sing mariachi and rancheras with our families and friends.

His songs are just as much our rancheras as anything by Vicente Fernandez, despite him being a pale British bloke from gloomy England. Both Chente and Moz express the anguish and awkwardness of loss, pain, love and desperation. Latinos are a people who feel and feel big, and The Smiths and Morrissey was another outlet to express our emotions. Particularly if we were outsiders, disappointing our parents with our weird clothes and weirder music.

We bring him flowers and cards, and express our concern when we know he is ill. It’s what we do for our family and friends who are hurting. We create bands in his honor, like the band Sweet and Tender Hooligans or Mexrissey, which does Spanish versions of Smiths/Morrissey songs and incorporates a Mexican sound. Think trumpets. The day Morrissey dies, I’m positive the Mexican flag will wave at half-staff and millions of pompadoured men and cat-eyed women will weep and light candles and play “I Know It’s Over.”

Morrissey is undoubtedly the patron saint of the sweet and tender Mexican. The Mexican who loves their culture – its music, its language, its passion, its art, its high regard for love and family – but also rejects its glorification of hyper-masculinity and antiquated gender norms.

The Mexican who cares about animals and sees the indignity in inequality. The Mexican who seems too soft to their parents and grandparents. That is, until the tequila flows. Then we’re all crying together.

There is a strong undercurrent of anglophilia in Mexican alternative culture. In the past I’ve written about Tijuana’s mod scene and attempted to understand how a subculture that grew as a direct response to post-war Britain had struck a chord with a group of Mexicans thousands of miles away from the foggy UK and who continue to keep the faith to this very day. The same curious connection exists with Morrissey and The Smiths.

Concurrently, my teens and early twenties were made up of countless nights dancing among shaggy-haired Mexicans to Blur, Pulp and, of course, The Smiths in a tiny Tijuana bar called Porky’s. The dance floor filled with screams of excitement when “This Charming Man” came on. The Mexicans that make up these subcultures are mostly working class and dealing with similar identity struggles British working class youth have encountered. There’s a shared experience there that seems to be more meaningful to the Mexican side, who have long adopted the style and sounds of British rock musicians. I’ve yet to meet any British people jamming out to Juan Gabriel or even Soda Stereo.

Morrissey, however, embraces his Mexican following and has adopted the culture to a certain extent. Some even call him an honorary Mexican. “I wish I was born Mexican,” he once told a crowd of Las Vegas concertgoers. He wrote a love letter to Mexico with the song “Mexico,” and gave a nod to his fans with “First of the Gang to Die,” about a Los Angeles gangster named Hector who meets his untimely end from a bullet in his gullet.

When he sang about the dichotomy between his Irish blood and an English heart, and I could relate as a Mexican-American living life on both sides of a wall. The music of The Smiths and Morrissey often gave me the words I couldn’t form as an angsty young woman carving an identity for myself. Morrissey helped me sing my life, and he’s had the same effect on millions of other Mexicans. So much so that we tacitly forgive him as he devolves further and further into a blithering uncle with a penchant for arrogant shit talk and offensiveness.

Like when he said, “I really like Mexican people. I find them so terribly nice. And they have fantastic hair, and fantastic skin, and usually really good teeth.” He also blamed the near extinction of rhinos on Beyonce, and okayed the use of beloved black writer and cultural critic James Baldwin’s image on a t-shirt that included the lyrics “I wear black on the outside / ‘Cause black is how I feel on the inside,” from The Smiths’ song “Unloveable.” And then his views on immigrants are just…no.

He makes it very hard to love him sometimes, and yet we do. Perhaps because we’ve taken him on as our own.

I couldn’t tell you the first time I heard The Smiths or Morrissey, but as a first-generation Mexican woman who was raised on both sides of the border, Morrissey’s presence in my life has been as prevalent as my mother’s incessant yelling, my father’s rancheras and the deep conflicts that occur when you navigate a life of division.

The border I crossed every day was a too-obvious metaphor for the split in my being, and Morrissey’s melancholy voice and lyrics provided the soundtrack to my coming-of-age, mirroring my own vulnerabilities, anger, humor, heartbreaks, fears and passions. Those passions are shared by Mexicans and other Latinos alike.

Source:mitu