Maricopa City deals with high pollutant levels, as EPA eyes new standards

By Khara Persad

Cronkite News

Click on the map above to get multiple years of readings from monitor sites around the state. (Cronkite News Service graphic by Khara Persad)

How they rank

Air-quality monitoring sites around the state, and their average readings for 2009-2011 for particulate matter of 2.5 micrograms (PM2.5)

• Cowtown, City of Maricopa: 13.3

• Durango Complex, Phoenix: 11.3

• Nogales: 11.1

• West Phoenix: 9.9

• South Phoenix: 9.9

• Yuma (Courthouse): 9.4

• North Phoenix: 9.3

• Casa Grande: 9.3

• Glendale: 9.1

• N. Phoenix (JLG Supersite): 8.4

• Mesa: 7.5

• Yuma (Supersite): 7.5

• Apache Junction: 6.9

• Flagstaff: 5.9

• Scottsdale: 5.6

• Tucson (Orange Grove): 5.4

• N. Tucson (Children’s Park): 5.4

• Prescott Valley: 4.3

• Peach Springs, Mohave: 4.2

Source: Environmental Protection Agency

WASHINGTON – The air gets so bad on some days that Marilyn Wyant has to wear a mask to travel around the City of Maricopa, or face suffering an asthma attack.

Wyant, the director of health services for the Maricopa Unified School District, said its nine schools now follow a color-coded flag system to warn students, teachers and parents about the air quality on any given day – as around 800 of the district’s 5,900 students were diagnosed with asthma.

“It’s become part of our everyday life,” she said.

Everyday life in Maricopa means living with the highest levels of particulate-matter pollution in the state, according to an analysis of Environmental Protection Agency monitor data from 2000 to 2010. The city’s monitor averaged particulate matter levels 50 percent higher than the next-highest monitor, in Nogales, and from 2006 to 2009 Maricopa was well above the federal standard for such pollution.

City officials don’t dispute the numbers but they call them misleading: The city’s monitor is located in the worst possible place, they say, near a dusty feedlot that is home to about up to 30,000 cows at a time.

“When cows get frisky, this leads to dust,” said Brent Billingsley, development services director at the City of Maricopa. “Frisky” is the term used to describe cattle on the move, which creates dust clouds.

But health and environmental officials note that the monitor is doing the job it was meant to do – measure fine particles in the air – and say it is wrong to focus on the monitor, noting that such pollution “breaks through our defenses” and settles deep in the lungs because of its small size.

“You can move the monitor until you get the results you want, but that’s not how you ensure healthy air,” said Sandy Bahr, director of Sierra Club’s Grand Canyon chapter.

Tougher air standards coming

The sparring comes just as the EPA is scheduled to announce an updated National Ambient Air Quality Standard for PM2.5 on Friday.

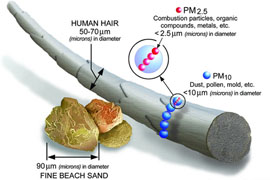

The pollution in question is PM2.5, a pervasive category of pollutants that consists of particles with a diameter of 2.5 microns or less. Under current federal standards, an average annual measure above 15 micrograms of PM2.5 per cubic meter of air is unacceptable.

The EPA is expected to toughen those standards this week. The question is how much.

“We’re always pushing for lower PM standards,” said Christian Stumpf, regional director of public policy at the Southwest chapter of the American Lung Association.

Stumpf said the association is pushing the EPA to drop the annual PM2.5 standard to 11 micrograms per cubic meter, a change it believes will save lives. The association estimates that such a change would reduce premature deaths from PM2.5 exposure by more than 35,000 a year nationwide.

But city and Pinal County officials argue that they are just starting to come into compliance with the current standards, which they said were not designed to measure dust particles like those found in the West. The PM2.5 standards are a better measure of power-plant emissions, they say.

“The regulations from the EPA seem geared toward the East and Midwest,” Billingsley said. But he conceded that the argument carries little weight with federal regulators.

“Ultimately, it comes down to what the EPA believes. The city looks bad, the monitor is placed in an unorthodox place, and this is the cause of the problem,” he said.

And what the EPA believes is that PM2.5 exposure is hazardous “from all sources,” said a spokeswoman, a position she said is based on the best scientific evidence.

Counting air quality

The EPA declared Maricopa a non-attainment area for PM2.5 in March 2011, meaning readings from the “Cowtown monitor” exceeded the federal standard. An average of the annual readings between 2006 and 2010 was 18.22 micrograms per cubic meter at Cowtown, the only monitor in the state to exceed the federal standard.

But local officials say the readings at Cowtown are better now than they were when the city was declared noncompliant. The Pinal County Air Control District said the latest readings it has available, from later in 2011, show PM2.5 had fallen to 13.24 micrograms per cubic meter.

“Historical levels (of PM2.5) have been elevated, but the trend is moving downward in recent years,” said Eric Massey, air quality division director at Arizona Department for Environmental Quality.

Kale Walch, deputy director at the Pinal County Air Quality Control District, said the best way to view the city’s data is to take three-year averages and compare them to the national standard. He said the three-year average in 2009 stood at 18.8 micrograms per cubic meter in Cowtown, dropped to 15.4 in 2010 and then 13.2 in 2011 – the same downward trend but a better overall number, he said.

“The numbers show there have been improvements in PM2.5, we have made some strides, and this trend can be maintained,” Walch said.

Cleaning by paving

Officials say they are taking short- and long-term measures to address the problem. One simple measure is watering the feedlots, which is required to keep down dust.

“This increases the moisture across the surface of the pens,” said Basilio Aja, executive director of the Arizona Beef Council.

Walch said that in addition to sprinklers for the cow pens, the feedlot operator also runs water trucks to keep down dust on nearby roads, many of which are not paved. The Cowtown monitor sits next to the Maricopa-Casa Grande highway, near cow feeding lots, a grain mill, an ethanol plant and dirt roads.

Aja also believes “open, unpaved dirt roads” are a large part of the problem.

While it is impossible to control the prevailing desert conditions, Billingsley said the city has gone to great lengths to improve air quality by paving dirt roads. With about 45,000 residents, the city’s dirt road ways see a lot of traffic. The city has paved about 500 lane miles, Billingsley said, with only seven more miles still unpaved.

“I don’t think there is anybody who has done more paving of roads in the last 10 years in the state of Arizona,” Billingsley said. He said the city has also dust-proofed the shoulders on existing roadways.

Long term, the city is working on a state implementation plan, in conjunction with ADEQ, to be submitted to the EPA for review by January 2014, Walch said. That plan will have to show not only that pollutant levels have been going down, “We have to prove to the EPA we can keep them there,” Walch said.

Massey said the first step in preparing the plan is to do a complete emission inventory to determine the sources of the particulates. But local officials say that as long as the monitor is in Cowtown, there are going to be problems.

“There’s no other monitor in Pinal County that’s misplaced like that,” Aja said. “If you put a monitor on an exhaust pipe, what kind of reading do think you’re going to get?”

Billingsley agreed, and noted that there are no homes within three miles of the monitor.

“We don’t agree with how it’s placed, but there’s nothing we can do about it,” said Billingsley, who said finding high pollution readings from the Cowtown monitor is about as surprising as finding snow on Mount Everest.

Location, location, location

An EPA spokesman responded to that argument by email, saying the agency “has reviewed the ADEQ and Pinal County monitoring networks, including the Cowtown Monitor, and has not found any issues.”

Bahr said local officials should worry less about the location of the monitor and more about the quality of the air it is capturing. Whatever the location, she said, “you still want air quality to be well.”

“It’s always interesting that the answer to poor air quality is to move the monitor,” Bahr said. “It’s not a good argument.”

ADEQ’s Massey agreed that questioning the monitor’s placement is irrelevant.

“The EPA has specific monitoring criteria, and it is something the state takes seriously,” Massey said.

Aja and Billingsley said they do care about the air quality, and their critics are wrong to focus on their complaints about the monitor’s placement.

“Of course we care about public health,” Aja said.

Dr. Barbara Warren, a physician and public health advocate in Tucson, said particulate matter is a real health concern and not just a matter of a little dust.

Fine particles cause inflammation and can block arteries that nourish the brain, Warren said. People suffering with asthma, heart disease, bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and other respiratory ailments are more susceptible to suffering with sickness and pre-mature death as a result of bad air quality.

“Children are more vulnerable to asthma, and there are about 6 million children in the United States with it,” Warren said.

For the roughly 800 students with asthma in the Maricopa school district, bad air quality poses health threats and can force limited or restricted recess. When PM2.5 is expected to top 35 micrograms per cubic meter in a single 24-hour period, the red flag goes up.

“On an orange-flag day pupils with health issues cannot go outside, while those without are limited to 15 minutes of play time,” Wyant said. On red days, everybody has to stay inside.

Wyant called the Pinal County flag program a success, saying it has protected hundreds of students from suffering asthma attacks.

“We used to see a lot of students in respiratory distress before the flag program,” Wyant said. “Now we use the flag system and it is way better, we don’t allow them to be exposed.”

‘Like a plastic bag over my lungs’

Wyant, who moved from New Mexico to Maricopa City about six years ago, said the air quality difference is tangible on bad days, even those in the yellow- to orange-flag range at times.

“I feel a difference on days when the air quality is bad,” said Wyant, 55. “I use an inhaler and a nebulizer.”

She said not being able to breathe during an attack feels like her lungs are being suffocated.

“It’s like a plastic bag is tied over my lungs, and I’m fighting against it,” Wyant said.

But she notes that bad air can be found anywhere, and there’s too much else in Maricopa for her to leave.

“It doesn’t matter where you live, you can’t escape air quality, really,” said Wyant, who said the flag system and her inhaler help her get by. “I don’t plan on leaving because of air quality in Maricopa.”